Despite a mild climate, forest fires are a serious problem in Romania

Romania has a temperate continental climate, which does not make it prone to forest fires. So why do so many of them happen? Fire risk is going to increase even further due to climate change – but the country seems not to be fully prepared for it yet.

Forest fire in Apuseni Mountains, Romania (photo: © Igor Sirbu/Shutterstock)

Romania’s climate is not like that of Spain and Portugal – we learned that at school. Romania has a temperate continental climate, which does not make it prone to forest fires. So why does Romania have so many of them? We spoke to several experts to find out how Romania compares with other Mediterranean countries in terms of wildfires, and what future can be expected amid a changing climate.

We already reported on bushfires in the Danube Delta, as well as crop burning on farms. Forest fires are another piece of the puzzle. What do all these things have in common? Humans.

EU reports suggest that 9 out of 10 vegetation fires are caused by humans. Fully 97 percent of them are caused by factors related to humans, according to retired general Ion Burlui, a former inspector-general of Romania’s General Inspectorate for Emergency Situations (IGSU) who has a PhD in forest-fire risk. “One of the main causes is the spread of fire to the forest from meadow or farmland cleared by the burning of dry vegetation,” explains the general.

“99 percent of forest fires are caused by human activities, such as the uncontrolled burning of pasture in spring and the burning of stubble after the harvesting of crops directly adjacent to forests,” confirm Romanian foresters from the Marin Drăcea Forestry Research and Development Institute (INCDS). Just one example: out of 216 fires recorded by the Râmnicu Vâlcea Forestry Guard, 171 involved farmland.

Wildfires in Europe

This article is part of a series of stories produced by PressOne in the framework of EDJNet’s large investigation on wildfires across Europe, co-funded by the Horizon2020 FIRE-RES project. In other articles, PressOne has looked at wildfires in the Danube Delta and at crop burning on farms in Romania.

The largest area of forest burned since 1956

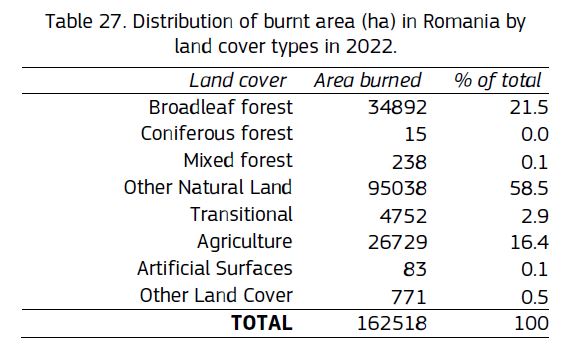

In 2022 in Romania, forest fires consumed an area of 13,141 hectares, for a total of 1,019 fires. This data comes from the Marin Drăcea Institute. The institute’s representatives also say that 2022 was the year with the largest area of forest burned since records began in 1956.

Source: San-Miguel-Ayanz, J., et al., Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2022, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2022.

To get an overview of the phenomenon, we requested information on forest fires from the relevant Romanian institutions, that is the Ministry of the Environment, the National Forestry Agency (ROMSILVA, which administers state forestry fund), county forest guards, and the Environmental Guard. Once again we had confirmation of how inaccurate the collection of data on wildfires currently is in Romania, as we received contradictory information from the various institutions.

According to the environment ministry, in 2022 there were 1,021 forest fires and bushfires. In the answer received from the Marin Drăcea Institute, the number of fires is 1,019, with the note that this data was also communicated to the environment ministry.

Meanwhile, ROMSILVA’s information was self-contradictory. In an official response sent to PressOne, ROMSILVA reported 856 forest fires in 2022, with an affected area of 10,185 hectares. But in the annual report published on the institution’s website, other data appears, mentioning 834 fires affecting 10,920 hectares.

565 hectares damaged in a single fire

Counties of Romania

From the data available to us, it appears that the top counties for forest fires are the South-West counties of Caraș-Severin, Gorj, Mehedinți and Dolj. Caraș-Severin also recorded the largest area affected by a single fire (565 hectares) in 2020.

In the summer of 2021, Raed Arafat, head of the Department for Emergency Situations, stated that most forest fires occurred in the Domogled-Valea Cernei National Park, a protected area and the largest national park in Romania, with an area three times the size of Bucharest. The park overlaps Caras-Severin, Mehedinți and Gorj – the counties most affected by forest fires.

Alexandru Teleagă is an environmental activist and a regular user of mountain trails in Caras-Severin. In October 2019, on a Saturday, he was on a hike to Arjana Peak, Cerna Mountains, when he saw a trail of smoke rising from a meadow. “From that sign, I could tell that the wind was blowing right up and was going to bring the fire into the forest. The fire was getting stronger – so I called 112”, says the activist.

According to the park administrator ROMSILVA, the fire started on agricultural land in the village of Cornereva and spread to the forest. An area of 38.5 hectares was ravaged: 28 hectares of forest and 10.5 hectares of farmland and meadow. The terrain was difficult, with forest growing on limestone, rocks and scree and without a water supply nearby – so the fire was only extinguished after four days. In the meadow, about 70-80 percent of the juniper vegetation burned, says Teleagă.

This photo is from May 2023 and shows the areas of alpine meadow affected by the 2019 fire. The burnt juniper has not recovered yet. Photo by Alexandru Teleagă.

A super-organism

One of the worst fires in Domogled National Park took place in 2013. It reached the scientific reserve, one of the most valuable areas in the park, and ravaged 114 hectares.

At that time, the IGSU’s inspector-general was Ion Burlui, who also led the intervention. “Compared to other forest areas in the country, Domogled has some specific features that increase fire risk: it is home to Mediterranean vegetation species with a high risk of fire, and the structure of the massif is rocky, with no springs on the slopes. In case of fire, water must be brought from the Băile Herculane lake, or from cisterns at the base of the slope”, explains Burlui.

Alpine meadow area affected by the 2019 fire in the Cerna Mountains. Photo: Alexandru Teleagă.

The 2013 primarily affected the litter, although the understory and canopy also suffered. In the case of litter fires, the dry vegetation on the ground burns, but not the trees. In understory fires, the soil is damaged and the trees may dry out as a result. A fire that reaches the canopy is the worst: “The forest is totally destroyed in such cases,” as the general puts it.

Ionuț Stetca is a forester and says that a forest can be considered a super-organism that reacts as a whole, regardless of where the fire reaches. “Any disturbance affects the whole organism. For example, if you burn an area of litter on the boundary between field and forest, which is very rich in diversity and where there are many birds and insects, this can lead to a multiplication of insects such as caterpillars, which can affect the whole forest,” explains the forester.

As the 2013 fire in Domogled reached the canopy, we asked ROMSILVA how ecosystems can recover. In 2018, the park administrator commissioned the Marin Drăcea Institute to carry out a reforestation study of 33.29 hectares of the park. The work began in autumn 2022 and was completed this spring. ROMSILVA told us that “the percentage of success [is] to be evaluated in autumn 2023”.

Fire and old trees

Sorin Petrovan is a senior researcher at Cambridge University specialising in biodiversity conservation. We asked him what happens when fire affects trees over 100 years old. This is what happened in July 2022 in the Rodna Mountains National Park.

“Old trees have a very complex function in the ecosystem, which you cannot substitute even under the best conditions. You can’t say, ‘I will cut down a 100-year-old tree, but that’s okay, I’ll put five more in its place’. It will take 60 years for those five trees to be able to perform any of the functions that the older tree provided”, explains Petrovan.

As a tree gets older, it develops lots of microhabitats. For instance, a lightning strikes it and makes a hollow in the top: near the hollow, a branch begins to rot, and this provides food for woodpeckers. “Bats, for instance, consume large quantities of mosquitoes. In the forest, they nest in this kind of microhabitat. So do owls that eat rodents. Pipits eat caterpillars, which would otherwise have a negative impact. In the forest, these kinds of complex systems are tied to old trees,” says the researcher.

He adds: “If you’ve opened up the area through inappropriate logging or burning, the soil is very unlikely to grow forest again. The moment you lose the forest, you will have massive erosion.”

Who intervenes?

In the event of a forest fire, there are three main channels of intervention. The first on the scene are foresters, who act on the basis of a fire protection plan and who are theoretically equipped to respond. However, we asked ROMSILVA for an inventory of its equipment, but no such inventory exists.

We did come into possession of the fire protection plan of a forestry estate overseen by the Focșani Forestry Guard. According to the document, the unit’s defence capacity is based on 9 employees. It has five vehicles for transporting people and can also call on nearby businesses for help.

The second channel of intervention is the local volunteer emergency service, explains retired general Ion Burlui. And the third is the military fire brigade, the ISU, which works in coordination with other institutions when necessary.

The Romanian state has declared that managing wildfire emergencies is an issue of national interest. Thus, in 2018 the “National Concept for Response to Forest Fires” was developed. This strategy document outlines how institutions with competences in the field should work together. If the national resources are insufficient, European assistance can be requested. At EU level there is the EU’s Civil Protection Mechanism, which can respond to natural and man-made disasters. Forest fires in Europe in 2022 led to the EUCPM being activated 11 times.

The national strategy also calls for fire-prevention measures “to protect life, property, and the environment”. According to Burlui, this means monitoring the forest floor, but also training response personnel and carrying out educational campaigns.

Roads every 500 metres

“Preventive measures are not cheap. High-capacity reservoirs, remote camera monitoring, and so on. […] We need to be able to build up water reservoirs in inland streams and rivers. Near Paris, I visited the Fontainebleau forest, which had access roads every 500 metres. If something happens, a car can enter from one side and reach the fire site,” points out the general.

Some forest rangers believe that Romania’s road network is an obstacle to putting out fires. For example, in the case of a forest in Focșani, only 40 percent of the roads are suitable for fire engines.

Sorin Petrovan, the Cambridge researcher, explains: “In the Mediterranean area, where places – such as those in Spain and Portugal – face the worst forest fires, there is a network of forest roads made specifically in order to fight fires. That is not cheap or easy to do, nor simple. When you talk about making access roads in a protected area, you open a Pandora’s box. You also facilitate access for people with all-terrain vehicles and thus, in the end, legal or illegal logging.”

We asked ROMSILVA if the forests under its supervision have exclusive fire roads, but we did not receive an answer. We made another request containing 15 similar questions, including on whether risk areas are mapped. We did not receive an answer to that either.

We were, however, informed of existing measures to prevent and fight fires. These include the updating of alarm plans, the monitoring of forest boundaries, as well as patrols and checks (we asked for a clear record of checks carried out, but again did not receive an answer). As regards video surveillance of the forest, ROMSILVA’s response was: “Through the forestry directorates, and after an analysis of the vulnerable areas, [ROMSILVA] will install video surveillance systems in accordance with the legislation in force.”

According to the MEP Diana Buzoianu, Romania is committed to video surveillance. “There are some measures that we have not taken yet, even though they are envisaged in the official plan. For instance, CCTV should already have been implemented in the forests,” she explains.

The Marin Drăcea Institute was a partner in a project called RO-RISK, coordinated by the IGSU, the national emergency inspectorate. It carried out a national risk assessment for forest fires, and hazard maps were drawn up. The project’s overall conclusion was that forest fires remain one of the most frequent natural disasters in Romania. The most affected area is in the south-west, in Gorj and Mehedinți counties. Researchers also say that “in the medium term, we expect the impact of forest fires to increase”.

Climate change fuels wildfires

Differences in climate and weather are what distinguish wildfires in the Mediterranean basin from those in Romania. “There are areas with much longer droughts and heat waves than we have. They also have a specific kind of vegetation which is more prone to fires than in Romania. Weather factors, such as long periods of low relative humidity and very strong winds, help to spread and sustain fires over much longer periods,” explains Cristian Mocanu, an expert on vegetation fires in the Mediterranean.

Tree bark is affected by fires. Photo Alexandru Teleagă.

But as the average global temperature rises, Romania will probably see its climate change from temperate continental to southern European. This will be conducive to more wildfires.

Bogdan Antonescu, a climatologist, elaborates: “With rising temperatures, there’s more evaporation. Since there’s no moisture reserve in the soil, vegetation dries out. That contributes to heat waves. And then you have prolonged periods of high temperatures, which dries out the vegetation and creates conditions for fires to spread.”

With climate change also come changes to the water cycle, he adds: “There are areas where you have less rainfall than in the past, and there are areas where you have more. For example, in recent years in Europe we have had periods of prolonged drought. Last year we had heat waves, on top of which we had periods of drought.”

Antonescu cites research showing how climate change is shifting northward the typical climate conditions of Mediterranean Europe. “What we see very clearly from the latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is that heat waves – which are major contributors to wildfires – will be more intense, more frequent and of longer duration than at present,” he says.

Vicious circle

Bogdan Antonescu warns that burning vegetation also releases carbon dioxide into the air, a greenhouse gas. This, of course, itself contributes to global warming, which in turn promotes wildfires.

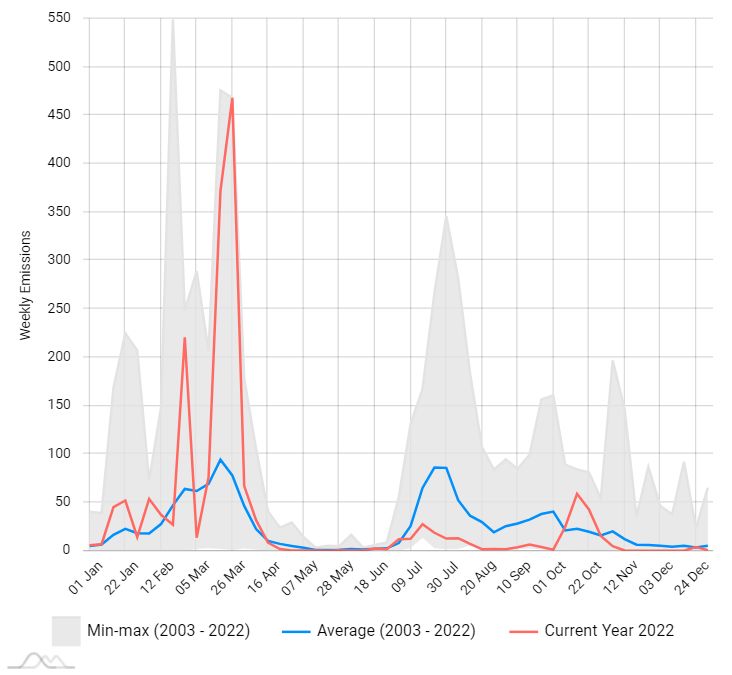

According to the IGSU, fires start to increase in March, which also translates into a sharp increase in carbon-dioxide emissions.

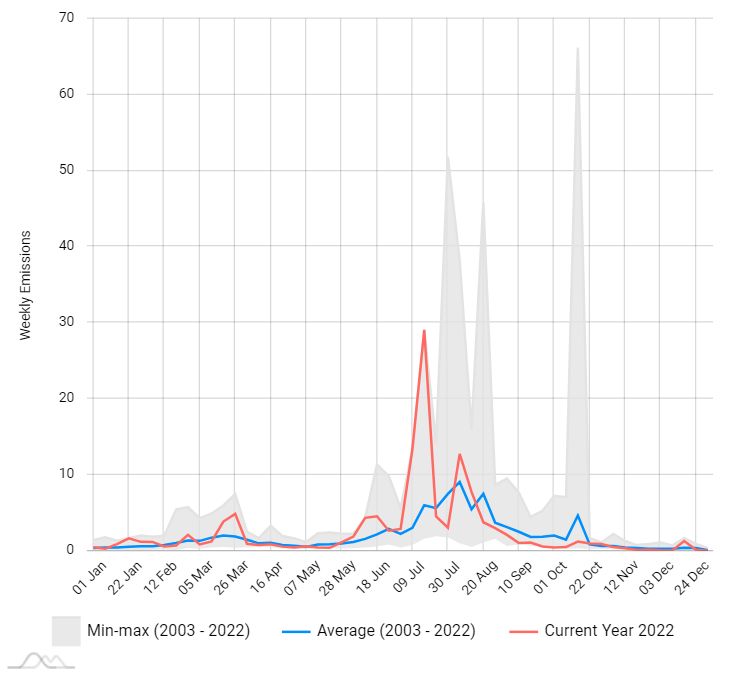

But carbon dioxide is not the only pollutant when it comes to vegetation fires. Black carbon (soot), which contributes to the small particulate matter known as PM 2.5, is also dangerous. “In most of the fires in mountainous areas, the contribution in terms of pollutants is predominantly PM 2.5. In the wildfires of the last 10 years in China, India and the Mediterranean basin, the proportion of PM 2.5 is over 50 percent,” Mocanu adds.

The European Union’s declared maximum annual limit for PM 2.5 values is 25 mg/m3. On a single day in July 2022, the annual limit was exceeded due to only one source: vegetation fires.

At EU level, according to EFFIS data, more than 837,000 hectares were affected by vegetation fires in 2022. This is also reflected in emissions.

According to data from the European Commission, the number of people exposed to extreme wildfires for at least 10 days a year will increase by 15 million if global warming reaches 3°C. Since 1980, 190,000 km² of Europe’s forests have been destroyed by wildfires – twice the area of Portugal. These fires cause €2 billion in economic damage every year.

How do other countries manage wildfires?

In countries such as the US, Australia and the UK, controlled fires are used to reduce the danger: dry vegetation is burned within a tightly controlled perimetre, so as to reduce the amount of dry biomass. Soran Petrovan, the Cambridge researcher, explains: “In the UK, reed burning is used by conservation organisations such as the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. But they use it within very strict parameters and do what’s called ‘adaptive management’. They take action in a single area only, they monitor what happens, then they make that data public, and based on that they decide whether to continue or not.”

The problem of wildfires has also been a headache for the authorities in Ireland. Initially, the burning of grassland and farmland was illegal and penalties were imposed. But uncontrolled fires continued. So the authorities, together with forestry officers, decided to produce a guide to teach people how to carry out controlled burning. In another guide published in May 2023, the European Union Civil Protection Knowledge Network – a federation of researchers, bodies and institutions involved in disaster management – presents examples of best practices adopted by some European countries to prevent forest fires.

For example, following its 2021 fires, Italy set up a technical committee involving national and local government. This body is to draw up a plan every three years on how to deal with fires. In Croatia, video surveillance has been used since 2003 to fight wildfires. The system consists of dozens of strategically placed cameras that automatically detect smoke and fire within a 10-km radius. Nearby Slovenia has developed an automated daily fire-risk forecasting system. It features a free web application that can be used by different stakeholders to assess fire risk and to help with interventions.

Spain and Portugal, meanwhile, have signed an agreement on mutual assistance in case of fires in border areas. The deal allows task forces from the two countries to act in unison within a 15-km zone of each other’s borders, even before a formal request for assistance is issued. One aim is to prevent fires from spreading across the border.

What is Romania doing?

As far as Romania is concerned, the Marin Drăcea Institute is a partner in the FirEUrisk project, which involves 38 organisations. It aims to improve risk-assessment systems, to put measures in place to mitigate risky situations, and to help adapt strategies to climate change.

As we have seen, up to 99 percent of forest fires are caused by humans. Romania’s Agricultural Payments and Intervention Agency can withdraw funds from farmers who set fire to farmland or meadows if those plots are registered for financial aid. In 2022, according to data received from the Ministry of Agriculture, such penalties concerned 1.94 percent of the total area of land for which funds were requested. From 2023, the agency says it will also use data from Copernicus satellites to check whether or not a farmer has burnt his or her land.

Restoring what has burned is usually laborious and costly. Mihai Zotta works for the Conservation Carpathia Foundation, which is trying to restore over 12,000 hectares of the Făgăraș mountains that were damaged by illegal logging. “Over a few years we have managed to restore 2,000 hectares. We started in 2013,” details Mihai Zotta. It has taken 10 years, but “We will not recover the functionality of the previous forest in another 10 years,” says Zotta.

This article was produced in the framework of FIRE-RES, a Horizon2020 project co-funded by the European Union focusing on extreme wildfires in Europe.

Original source: https://pressone.ro/romania-arde-iii-cum-a-ajuns-tara-noastra-pe-locul-doi-in-ue-la-incendii-de-vegetatie-cu-toate-ca-avem-o-clima-care-ne-protejeaza

This material is published in the context of the "FIRE-RES" project co-funded by the European Union (EU). The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project. Responsibility for the content lies solely with EDJNet. Go to the FIRE-RES page

This material is published in the context of the "FIRE-RES" project co-funded by the European Union (EU). The EU is in no way responsible for the information or views expressed within the framework of the project. Responsibility for the content lies solely with EDJNet. Go to the FIRE-RES page